What Is an Argument Agains Discrtionary Relase

Grading the parole release systems of all 50 states

By Jorge Renaud Tweet this

February 26, 2019

From abort to sentencing, the process of sending someone to prison in America is full of rules and standards meant to guarantee fairness and predictability. An incredible amount of attention is given to the process, and rightly and so. But in sharp dissimilarity, the processes for releasing people from prison house are relatively ignored by the public and by the police. State paroling systems vary so much that information technology is almost impossible to compare them.

Xvi states take abolished or severely curtailed discretionary parole,1 and the remaining states range from having a system of presumptive parole — where when sure conditions are met, release on parole is guaranteed — to having policies and practices that make earning release almost impossible.

Parole systems should give every incarcerated person ample opportunity to earn release and take a off-white, transparent process for deciding whether to grant it. A growing number of organizations and academics have called for states to adopt policies that would ensure consistency and fairness in how they identify who should receive parole, when those individuals should be reviewed and released, and what parole conditions should be attached to those individuals. In this study, I accept the best of those suggestions, assign them point values, and grade the parole systems of each state.

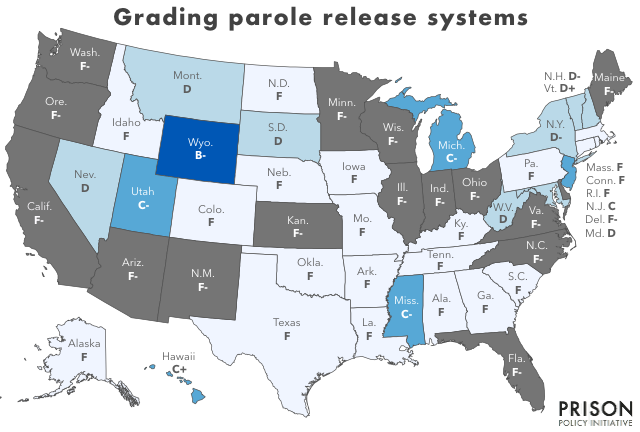

Sadly, most states show lots of room for improvement. But one state gets a B, five states get Cs, eight states become Ds, and the balance either get an F or an F-.

| Land | Grade | State | Course | State | Grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | F | Louisiana | F | Ohio | F- | ||

| Alaska | F | Maine | F- | Oklahoma | F | ||

| Arizona | F- | Maryland | D | Oregon | F- | ||

| Arkansas | F | Massachusetts | F | Pennsylvania | F | ||

| California | F- | Michigan | C- | Rhode Isle | F | ||

| Colorado | F | Minnesota | F- | South Carolina | F | ||

| Connecticut | F | Mississippi | C- | South Dakota | D | ||

| Delaware | F- | Missouri | F | Tennessee | F | ||

| Florida | F- | Montana | D | Texas | F | ||

| Georgia | F | Nebraska | F | Utah | C- | ||

| Hawaii | C+ | Nevada | D | Vermont | D+ | ||

| Idaho | F | New Hampshire | D- | Virginia | F- | ||

| Illinois | F- | New Jersey | C | Washington | F- | ||

| Indiana | F- | New Mexico | F- | West Virginia | D | ||

| Iowa | F | New York | D- | Wisconsin | F- | ||

| Kansas | F- | North Carolina | F- | Wyoming | B- | ||

| Kentucky | F | North Dakota | F |

| State | Class | State | Form | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | F | Montana | D | |

| Alaska | F | Nebraska | F | |

| Arizona | F- | Nevada | D | |

| Arkansas | F | New Hampshire | D- | |

| California | F- | New Jersey | C | |

| Colorado | F | New Mexico | F- | |

| Connecticut | F | New York | D- | |

| Delaware | F- | North Carolina | F- | |

| Florida | F- | North Dakota | F | |

| Georgia | F | Ohio | F- | |

| Hawaii | C+ | Oklahoma | F | |

| Idaho | F | Oregon | F- | |

| Illinois | F- | Pennsylvania | F | |

| Indiana | F- | Rhode Island | F | |

| Iowa | F | S Carolina | F | |

| Kansas | F- | South Dakota | D | |

| Kentucky | F | Tennessee | F | |

| Louisiana | F | Texas | F | |

| Maine | F- | Utah | C- | |

| Maryland | D | Vermont | D+ | |

| Massachusetts | F | Virginia | F- | |

| Michigan | C- | Washington | F- | |

| Minnesota | F- | W Virginia | D | |

| Mississippi | C- | Wisconsin | F- | |

| Missouri | F | Wyoming | B- |

For the details of each country'south score come across Appendix A. The xvi states with an F- made changes to their laws that largely eliminated, for people sentenced today, the ability to earn release through discretionary parole. For more on these states, see the methodology.

How we graded and what distinguishes a fair and equitable parole organization.

To assess the fairness and disinterestedness of each country'southward parole system, we looked at five general factors:

- Whether a country'south legislature allows the parole board to offer discretionary parole to most people sentenced today; (20 pts.) ⤵

- The opportunity for the person seeking parole to meet face-to-face with the lath members and other factors about witnesses and testimony; (xxx pts.) ⤵

- The principles by which the parole board makes its decisions; (30 pts.) ⤵

- The degree to which staff help every incarcerated person ready for their parole hearing; (twenty pts.) ⤵

- The degree to which the parole board is transparent in the way it incorporates testify-based tools. (20 pts.) ⤵

In improver, we recognize that some states have unique policies and practices that help or hinder the success of people who have been released on parole. Nosotros gave and deducted up to 20 points for these policies and practices. For case, we gave or deducted some points for:

| Helpful factors | Harmful factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Does not prohibit individuals on parole from associating with each other or with anyone with a criminal history (5 pts.); | Explicitly prohibiting individuals on parole from associating with others nether supervision, or with anyone who has a criminal record (5 pts.) | |

| Capping how long someone can be on parole (5 pts.) or allowing individuals to earn "good time" credits that they can apply toward shortening their time on supervision (5 pts.) | Allowing the lath to extend the period of supervision past the actual end of the imposed sentence (v pts.) | |

| Does not require supervision or drug-testing fees. (v pts.) | Requiring individuals on parole to pay supervision or drug-testing fees (v pts.) |

Does the state'southward sentencing structure empower a parole lath to review people for possible release on discretionary parole? (20 pts.)

Parole boards can but review individuals who the legislature (and sometimes judges) say they can. Xvi states passed laws effectively denying the possibility of parole for most anybody committing crimes subsequently those laws went into effect. To be sure, many of the remaining 34 states deny parole for individuals committed of sure crimes, simply however offer discretionary parole to the majority of incarcerated individuals at some signal in their sentence. Those 34 states all received twenty points. The states that take abolished discretionary parole received zero points and their procedures (for people convicted under the old law) were not evaluated further.

Parole hearings: Who gets a seat at the tabular array? (30 pts.)

Unlike what happens in the movies, most parole hearings don't consist of a few stern parole board members and one sweating, nervous incarcerated person. Most states don't take contiguous hearings at all, and instead do things similar transport a staff person to interview the prospective parolee. The staff person and then sends a written report to the voting members, who each vote (perhaps in isolation), and the incarcerated private never has a risk to present their case or present their parole plans to the voting members, or perhaps to speak to their crime, or to rebut any wrong information the board may have. On the other hand, nearly states, by legislative mandate, requite prosecutors and offense survivors a voice in the process. I accept 5 metrics by which I rate whether or not a state has robust practices when it comes to parole hearings.

- The lath should mandate face-to-face parole hearings. (15 pts.) Few people would hire someone, or hire a room to someone, or purchase a house from someone without start sitting downwardly and having a chat. A person seeking freedom deserves to sit down downwards and face those who will deny or approve that liberty. The voting members should run into and speak to the person to whom they are granting or denying freedom. (And by see, we don't hateful via telephone or video conferencing.2)

- There should exist a process past which someone seeking release can claiming incorrect information that the lath may use to deny parole. (6 pts.) A parole decision is ofttimes based on information provided by outside law enforcement agencies, or by prison gang intelligence officers, and that may be wrong or outdated. It is of import that at that place exist an opportunity to make the parole board's determination more accurate.

- Prosecutors should not be permitted to weigh in on the parole process. (iii pts.) Their voices belong in the courtroom when the original offense is litigated. Decisions based on someone's transformation or current goals should not be contaminated by outdated data that was the basis for the underlying conviction or plea bargain.

- Survivors of vehement crimes should not be immune to exist a function of the parole-decision process. (3 pts.) The parole process should be about judging transformation, but survivors take lilliputian testify every bit to whether an individual has changed, having not seen them for years. A truly restorative collaboration would ask survivors of crime for their help in crafting transformative, in-prison programming for individuals convicted of violent crimes, merely would not allow their testimony to influence parole decisions.

- Supportive testimony should be encouraged. (3 pts.) Anyone who has had a day-to-day interaction with the incarcerated person and anyone who intends to offer tangible back up to the person seeking parole should exist allowed to evidence in person. Information technology is obvious that a person with a substance abuse trouble would do good from a ride to AA meetings and why a parole board would benefit from an in-person inquiry into that volunteer's dedication. On the other hand, many states have rules that prohibit correctional staff — who are oftentimes the only people who take had day-to-mean solar day contact with the incarcerated person and can speak to their behavior and to their recent on-the-job performance — from testifying at parole hearings.

Parole principles: Who is eligible for parole and are they treated fairly? (30 pts.)

Certain principles should be nowadays in a fair parole arrangement. Practise all incarcerated individuals have a chance to earn parole? Do they understand what is expected of them? If they fulfill all the criteria expected of them, does the parole board grant parole or deny parole for other, more than subjective reasons? And if the board denies parole, how often are individuals reviewed once more? I graded states on the extent to which their parole systems reflect those principles.

- Every private in prison should be eligible for parole. (12 pts.) In 16 states the pool of individuals eligible for parole is rapidly diminishing because state legislatures take stripped their parole boards of the power to grant release but to a dwindling number of individuals sentenced decades ago. Many other states have Truth in Sentencing statutes in place, which means individuals are not eligible for parole until they have almost completed their sentences. And at to the lowest degree six states have almost a quarter of their incarcerated population serving life without parole, or sentences so long that they corporeality to virtual life.

- Each state should have presumptive parole. (9 pts.) This policy gives every incarcerated person a list of specific things they must do to make parole, all but guaranteeing their release at a predetermined date if they fulfill the state's requirements. This would inject fairness into the system and let incarcerated persons and their families to ameliorate prepare for release.

- Parole board members should not utilise subjective criteria to deny parole. (6 pts.) Some boards and members base their decisions on criteria then subjective it is unlikely 2 people would agree on whether those criteria take been met. In addition, parole denials are oftentimes based on static factors that tin never be changed or are across the control of the incarcerated individual. The well-nigh common reason for denial is a version of "serious nature of the law-breaking," which will e'er retain the same nature and is just a way for the board members to say, "Come back next time." All too ofttimes, parole boards will review an incarcerated person who has satisfied all of the typical requirements to be released then denies that person for subjective or static factors. Such denials send the harmful message that the parole board neither recognizes nor rewards transformation.

- No more a twelvemonth should elapse between a parole denial and a subsequent review. (3 pts.) Some states, such as Texas, allow up to ten years to elapse between reviews. A parole denial by the board in a robust system should only be based on factors such equally non-participation in required programming or recent disciplinary infractions. A year is more than sufficient for the incarcerated individual to address reasonable, objective, denials similar these.3

Preparation: If you get 1 shot at freedom, shouldn't the country help you get ready? (20 pts.)

A parole hearing could exist someone'southward only shot at freedom for years. If they don't know what programs the board expects them to take, or what information they may have to challenge, and if they tin can't testify to the board they have possible employment and a identify to stay, the board isn't going to let them get. Preparation matters, and I advise ii metrics to judge states past how well they assist people prepare for their parole hearings:

- Departments of Corrections should provide instance managers to each person within vi months of their arrival in prison house. (10 pts.) These case managers would help inform incarcerated persons what programs they needed to take, piece of work with those persons to fix for the hearing itself, and connect them to outside agencies after parole was granted.

- Every incarcerated person should accept admission to any documents or records the parole board relies on to make its decision. (10 pts.) Parole boards brand their decisions based on a person's criminal history and current offense, and every incarcerated person should exist able to speak to both in the presence of the board.

Transparency: Tin can the public empathize the parole board's decisions? (20 pts.)

One of the strongest critiques of land parole systems is that they operate in secret, making decisions that are inconsistent and bewildering. Neither the individuals beingness considered for parole nor the general public understand how parole boards decide who to release or who to incarcerate further. When parole systems reject people for arbitrary or arbitrary reasons, they unintentionally, but to devastating issue, tell incarcerated people that their transformation does not thing. And the public, who is paying for the criminal justice system, deserves to know how it works and how well it works.

Many states have begun to rely on parole guidelines and validated run a risk assessments as a mode to step back from the entirely subjective decision-making processes they accept been using. These instruments accept their own deficiencies, merely states that utilise them and provide the public access to that decision-making process were graded higher than states that refuse to pull dorsum the parole-determination curtain.

Transparency can exist measured in iii means:

- Parole boards should take guidelines to assist them make unbiased parole decisions, and those guidelines should be shared with the public. (8 pts.) Fair processes don't thrive in the dark. More than parole boards take turned to parole guidelines and validated risk assessments as a style to move away from "gut decisions," and as a way to give themselves more encompass for hard political decisions. Some states volition create their ain instruments from scratch, without having them validated scientifically for bias, and the public deserves to know what criteria is being used to release people into their customs, or to deny community members their freedom.

- Parole boards should effect yearly, public reports that explain deviations from outcomes recommended past parole guidelines. (6 pts.) Institutions with oversight over parole boards should receive reports detailing release rates and their deviations from recommended guidelines and assessments. While parole boards are withal expected to exercise personal discretion — otherwise, all parole decisions could be made by a figurer — parole boards should exist required to publicly explain why they might be consistently denying release when published guidelines recommend release.

- Individuals who are denied parole and fit all the requirements should exist able to appeal a denial and become either a rehearing or a credible explanation for that denial based on objective factors. (6 pts.) Every state seems to accept a version of a statute that claims, "Parole is not a right; it is a privilege." However, incarcerated individuals should have a reasonable expectation that they volition be released if they are eligible for parole, if they take completed all required programming, if they have no major disciplinary infractions, and if they have housing and employment waiting for them.

Methodology

This report relies heavily on the publications of the Robina Found of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota, which centralize many important details well-nigh parole eligibility, hearings, and post-release policies and conditions.

Our listing of sixteen states that have abolished discretionary parole is based on the Robina Establish'due south classification of states as having either largely a determinate — without discretionary parole — or indeterminate — with discretionary parole — system. (See sidebar)

Our policy suggestions — and the relative point values — are our ain, but the information for 27 of usa is based on the Robina Institute's first-class series Profiles in Parole Release and Revocation: Examining the Legal Framework in the United States.5 For the seven states with indeterminate sentencing systems that the Robina Institute has not published profiles for (Mississippi, Montana, N Dakota, Tennessee, Due south Carolina, South Dakota, and Due west Virginia), Prison Policy Initiative volunteers Eva Kettler, Sari Kisilevsky, Joshua Herman, Simone Price, Tayla Smith and I delved into statutes and parole lath policies to collect the necessary data. The sourcing for each state is in Appendix A. Additional data about how these policies are reflected in grant rates, technical violaton rates and other result metrics are available in the appendix to my earlier report Viii Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences.

Our intent with the scoring was to make it possible to compare systems that are both very different and very circuitous in a way that will brand sense across land lines. In particular, nosotros tried to give factors that nosotros felt were more than important a greater weight. Other advocates — and some state leaders — may disagree with some of our findings of fact or with the weights that nosotros gave to diverse factors that make up a off-white and equitable parole system. We welcome new information and factual corrections, and encourage our readers with different ideas on how parole should work to publish alternative analyses with their own scoring systems.

Four of the sections require more than comment:

- We believe that parole decisions should be made on objective criteria and that subjectivity should exist prohibited. The decision to release someone should be based on a number of factors — participation in educational and vocational programs, in-prison disciplinary history, and other verifiable metrics that signal personal transformation. All too often, denials for subjective reasons like the "gravity of the offense" or whether the release will "lessen the seriousness of the offense" serve only to diminish the motivation necessary for change. Unfortunately, only Michigan gets full credit for explicitly prohibiting subjectivity, and xvi states earned zero points considering their statutes specifically list examples of subjective excuses to deny parole. For this reason, we gave fractional credit to 17 states whose statutes refrained from encouraging denials for subjective reasons.

- Nosotros believe that prosecutors should not be immune to weigh in on parole decisions. No states prohibit prosecutorial input, so we gave our highest score here — three points — to those states whose statutes were silent on this matter. We gave two points to states that alerted prosecutors only after parole had been granted. States that allowed input from prosecutors (usually too requiring that the prosecutor ask or register for notification of a parole hearing) received one point, and zip points were given to states that mandated prosecutors be notified earlier all parole hearings.

- We believe that every incarcerated person should be given an opportunity to be paroled, so we gave points to states past the share of their prison population that was eligible in 2016 for release on parole. This is an important factor considering information technology demonstrates how many people are statutorily eligible to be released. This is likewise an imperfect mensurate, for several reasons. Some states practice not report the necessary data; the existing data does not reverberate how many people will never be statutorily eligible to exist considered for release, and in addition, existing parole policies could influence this effigy. For example, a parole board that refuses to release people would create a higher pct of individuals eligible for release, and a parole board that released most anybody at the first opportunity would have a lower percentage of incarcerated individuals eligible for release. To our knowledge, there is not yet a multi-state comparable way to determine: of the people sent to prison in a given year, how many of those will be considered for release before their maximum release appointment? And of those people, how many volition be eligible for consideration significantlyhalf-dozen earlier than their maximum release engagement?

- Nosotros believe that transparency requires parole boards to produce annual reports to the public and the legislature that include statistics on parole denials and justifications for those denials, particularly when those denials contradict whatever guidelines given to the parole board. Because all parole boards issue reports, nosotros gave the total 6 points to 13 states that require the parole board to publish reports with enough detail for the legislature to hold the board accountable, and cypher points to all other states.

I idea iii post-release weather condition were worthy of singling out:

- Prohibiting an individual from associating with someone on parole or who has a criminal record;⤵

- Limiting how long someone can be on parole, or conversely, imposing additional fourth dimension past what the original sentence called for; and⤵

- Imposing supervision, drug testing, or electronic monitoring fees.⤵

Re: clan. This prohibition is based on a belief that merely beingness in the visitor of some other person on parole — or who has a criminal tape, regardless of how long ago the actual law-breaking occurred — will invite criminal behavior. This policy ignores the widely-accepted idea that the mentorship and guidance of someone who has gone through a negative experience — be it incarceration, cancer, divorce, substance abuse, the expiry of a spouse or child — is affirming and positive. Lastly, denying those leaving prison the right to acquaintance with others similar them ignores the powerful impact on local, country, and national criminal justice policy reform by groups of formerly incarcerated individuals, many of whom are on parole, all of whom have criminal histories.

Re: time limits. I gave points to states that provide one or more mechanisms to shorten parole because there is no prove that unending supervision results in anything other than college recidivism rates. (Recall that currently people are rarely granted parole unless they are accounted a depression hazard of committing another law-breaking.) Meaningful supervision when someone showtime leaves prison house can exist positive, if information technology is not overly restrictive and goal-oriented instead of sanction-oriented.9 However, many states upshot a boiler-plate set of weather that are not tailored to individual needs, and thus exercise not contribute to successful reentry. Equally Massachusetts officials readily admit, "by virtue of existence under supervision in the community, an inmate may have a higher likelihood of re-incarceration." Shockingly, a few states fifty-fifty give parole boards the power to extend supervision past the end of the imposed sentenceten — a devastating policy with dubious legality.

Re: fees. Finally, very few individuals have the economic means to comply with the assortment of fees that some states impose. While these states normally claim to waive fees depending on the released individual's capacity to pay, in truth, parole officials pressure level newly released people to pay as much and equally quickly as possible and threaten to impose sanctions otherwise. That ignores two truths:

- Most no i leaving prison has assets, wealth, or savings.

- Many individuals leaving prison have other financial obligations, including child support, restitution, and unpaid fines.

Individuals should not bear the cost of their incarceration. Supervision is simply an extension of that cost.

To exist sure, some states have quirky11, by and large punitive, conditions of supervision that might warrant point deductions, but we choose not to do that because it was not possible to accept a comprehensive review of these conditions that would allow for truly fair comparisons between states.

- Appendix A:

How each state did on our 15 factors and the number of points for each, plus the extra points added or removed for each land.

Acknowledgements

A written report of this telescopic cannot be written without the help of others. I am deeply indebted to the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the Academy of Minnesota for their invaluable series on state parole polices which centralize many important details about parole eligibility, hearings, and post-release policies and conditions. Eva Kettler, Sari Kisilevsky, Joshua Herman, Simone Price, and Tayla Smith helped dig through parole policy and statutes to make full in details from states not yet covered past the Robina Plant and Mack Finkel prepared the analysis of the National Corrections Reporting Program data to evidence how many people in each state are currently eligible for parole hearings.

One challenge with writing a report like this is keeping it centered on the experience of people hoping for release on parole while also making sure that this report is relevant in all states, and to this end I am particularly thankful for the feedback of Laurie Jo Reynolds and Alex Friedmann who helped improve this report on a very short deadline.

Finally, I give thanks my Prison house Policy Initiative colleagues for support and encouragement, especially Peter Wagner for patiently editing and helping me develop the scoring arrangement and organize the land-past-country information in a form that will be useful to other advocates.

Jorge Renaud is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. He holds a Masters in Social Work from the University of Texas at Austin. His piece of work and research is forever informed by the decades he spent in Texas prisons and his years as a community organizer in Texas, working with those nearly afflicted past incarceration. His most recent report was Eight Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences (November 2018).

marlowsaidecalown.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/grading_parole.html

Post a Comment for "What Is an Argument Agains Discrtionary Relase"